2.2. Git basics¶

Now let’s learn to start version controlling some files Git!

2.2.1. Checking if Git is installed¶

First thing’s first, you will need access to a bash shell or mac Terminal (see Chapter 1) and to check if Git is installed. Open a shell and type git --version.

git --version

#git version 2.17.1

If there is a version number, great! Skip to Configuring your Git.

If there is no version number, you will need to install Git (this requires administrator access).

In bash, you can run:

sudo apt-get install git

For other Linux distributions, find guidance here.

For Mac, the git --version command should have prompted you to install it.

For Windows, you should can get access to a bash shell in any of the ways listed here. In that shell, you can use all of the bash commands to install Git and complete the rest of this chapter.

2.2.2. Configuring Git¶

The first thing to do when using git on a new machine is to let Git know who you are so that you get credit for your commits. To do this, we’ll use the git config --global command (--global configures all of your repos, while --local configures a single repo only).

Note: For your email, use the same one that you used to make your GitHub account (if you have one), or the one you plan to use for GitHub.

git config --global user.name "<FirstName FamilyName>"

git config --global user.email "<your.email@somewhere.com>"

2.2.3. Git init¶

In your shell, create a new directory called myfirstrepo and change directories to enter it.

mkdir myfirstrepo

cd myfirstrepo

Let’s make myfirstrepo/ a Git repository using git init.

Note: I will use the comment (#) symbol to show you what the output looked like on my computer so that you can follow along. The exact paths and wording may be slightly different on your machine.

git init

# Initialized empty Git repository in ~/projects/myfirstrepo/.git/

You can check that the .git folder was created with ls.

ls

#

Oops, since it starts with a ., the .git folder is hidden, so we need to use the --all or -a flag for ls.

ls -a

# . .. .git

Great! That’s all there is to it. Git will now track all changes we make to files in myfirstrepo/.

2.2.4. Make some changes¶

Let’s make a new file and see if Git notices. Let’s use our the bash redirection trick to make a new file with some text in it.

echo 'Hello World!' > file1.txt

Since Git is tracking myfirstrepo, it should have noticed the change.

2.2.5. Git status¶

You can always check what Git is seeing with git status.

git status

# On branch master

# No commits yet

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# file1.txt

# nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Git status tells us that we have an untracked file in our directory, meaning git won’t snapshot this file yet!

2.2.6. Git add¶

Before we commit file(s) to history, we must first add them them to the staging area with the add command.

git add file1.txt

git status

# On branch master

# No commits yet

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

# new file: file1.txt

Now Git status shows a new file: file1.txt in the staging area (i.e. under “Changes to be committed”). We can keep using git add to collect as many files as we want in the staging area before actually making a snapshot.

2.2.7. Git commit¶

Once we are happy with all of the staged files, we can use commit to make a snapshot that will be remembered in our Git history. Let’s make our first commit (remember to write descriptive commit messages!).

git commit -m "Add hello world to file1.txt"

# [master (root-commit) 8a7625f] Add hello world to file1.txt

# 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

# create mode 100644 file1.txt

Great! Let’s double check that everything got cleared from the staging area with one more git status.

git status

# On branch master

# nothing to commit, working tree clean

2.2.8. Git log¶

Where did our commit go? Into history, which we can check on at any time with the git log command.

git log

# commit 677ae89418559186a3fa49f726a3ab9bbe97cff3 (HEAD -> master)

# Author: Christian Tai Udovicic <cj.taiudovicic@gmail.com>

# Date: Sun Jan 1 07:00:00 1984 -0700

# Add hello world to file1.txt

Git log shows us the commit ID, author, date and commit message that we provided. After many commits have been made to a repository, git log can help us track down when certain changes were made and by whom.

2.2.9. TL;DR Tracking files with Git¶

The Too Long; Didn’t Read summary:

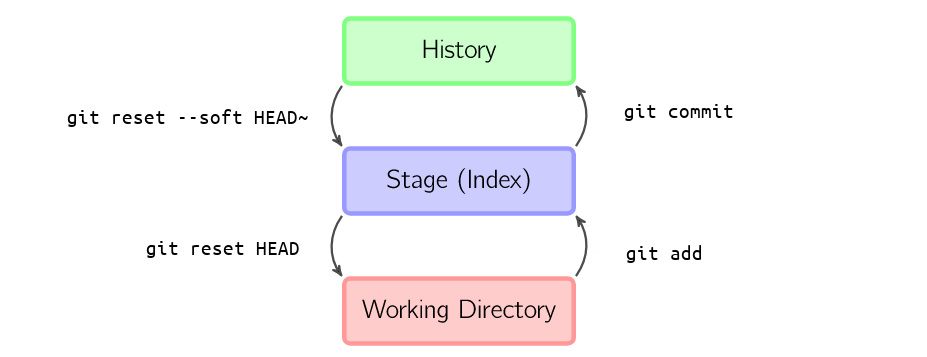

A file can be in one of “3 locations” according to Git:

The working directory: the most recent changes to your files in your repo

The staging area: new or updated files ready to be committed

In history: all commits (snapshots) since the start of the repo

You can move file(s) from your working directory to the staging area with git add.

You can then move all files in the staging area into history (i.e. make a snapshot) with git commit. This is summarized in the following figure.

2.2.10. Practice: multiple files¶

This time, let’s add a couple files to a commit. You can add as many files as you’d like to each commit - all changes in the staging area will be included in a commit.

Let’s make 3 files, and add two of them to the staging area. We can use the touch command to create new empty files.

touch good_file.doc

touch great_file.py

touch bad_file.xls

ls

# bad_file.xls file1.txt good_file.doc great_file.py

Say we want to make a commit with good_file.doc and great_file.py because we’re finished with them, but we’re still working on bad_file.xls and aren’t ready to commit it yet.

Let’s add just the first two to the staging area with git add.

git add good_file.doc

git add great_file.py

git status

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

# new file: good_file.doc

# new file: great_file.py

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# bad_file.xls

Here, git status tells us that two of our files are in the staging area and ready to be committed, but bad_file.xls is simply in the working directory and will not be included in this commit.

Now let’s commit these two files. Don’t forget the descriptive commit message!

git commit -m "Add good and great files"

Let’s check that our new commit is in history with the git log command.

git log

# commit cbc5a6ea58976cb5c0e5f0eb2ec5a2ca5da38f6c (HEAD -> master)

# Author: Christian Tai Udovicic <cj.taiudovicic@gmail.com>

# Date: Sun Jan 1 07:01:00 1984 -0700

# Add good and great files

# commit 677ae89418559186a3fa49f726a3ab9bbe97cff3

# Author: Christian Tai Udovicic <cj.taiudovicic@gmail.com>

# Date: Sun Jan 1 07:00:00 1984 -0700

# Add hello world to file1.txt

Git log can be pretty verbose. Let’s make the output cleaner with the --oneline flag.

git log --oneline

# cbc5a6e (HEAD -> master) Add good and great files

# 677ae89 Add hello world to file1.txt

Now we see there are 2 commits - one per line, from most recent to oldest. The HEAD -> master tells us that we are currently located at the most recent commit on the default branch called master (we will explore branches in the next lesson).

2.2.11. Git reset¶

Say we committed something by mistake, or want to revert our repo to an older version. To do this we use the git reset command!

The git reset command needs a commit ID to tell it which point in history you want to reset to. In my example above, the commit I want to revert to is 677ae89, but yours will be a different string of letters and numbers shown by git log. You can revert to any point in history by specifying the commit ID you’d like to return to.

Git reset HEAD

While we can git reset <commit ID> on the ID of the previous commit if we just want to undo our last commit, we can use the useful shortcut git reset HEAD~1.

The shorthand HEAD~<number> gives the current location of HEAD minus the <number>. In our case HEAD~1 would be the previous commit (8a7625f, in my case). Likewise, HEAD~2 would be the second-last commit, HEAD~3 would be third-last, etc.).

Reset options

Git has 3 options for resetting commits:

--softdumps all of the reverted changes into the staging area (used for quick updates, maybe you forgot to stage a file and want to add it to this commit)no flag will dump changes into the working directory (you will need to re-stage all changes you want to commit)

--hardshould be used with caution: it completely deletes all changes since the commit you are reverting to! Use this only if you know you want to delete all changes since a particular commit.

2.2.12. Practice: Git reset¶

Ok, let’s revert our last commit (HEAD~1) and put the changes back into the staging area with the --soft flag.

git reset --soft HEAD~1

git status

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

# new file: good_file.doc

# new file: great_file.py

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# bad_file.xls

Great, now that our changes are back in the staging area, we can confirm that the last commit was removed from history:

git log --oneline

# 677ae89 (HEAD -> master) Add hello world to file1.txt

The second commit was removed and HEAD was moved back to our “hello world” commit.

Now, say we decided against committing good_file.doc and only want to commit great_file.py. We can remove items from the staging area at any point with the normal git reset command.

git reset good_file.doc

git status

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

# new file: great_file.py

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# bad_file.xls

# good_file.doc

Now great_file.py is staged and ready to be committed! Let’s commit it with a new, descriptive commit message.

git commit -m "Add great file"

git log --oneline

# d0051d1 (HEAD -> master) Add great file

# 677ae89 Add hello world to file1.txt

Great! Now we have a brand new commit (with a new ID) which includes just the changes to great_file.py that we wanted.

2.2.13. Git commit –amend¶

We just learned how to revert the previous commit make a small change and re-commit it. This can be done in one step with the shortcut git commit --amend.

Say we now want to include bad_file.xls in our most recent commit. We can add it to the staging area and then use git commit --amend to include it in the previous commit. If we want the commit message to remain the same, we can add the --no-edit flag.

git add bad_file.xls

git commit --amend --no-edit

git status

# On branch master

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# good_file.doc

# nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Now bad_file.xls has been added to our previous commit. Let’s see if anything changed in our Git history:

git log --oneline

# c250ab6 (HEAD -> master) Add great file

# 677ae89 Add hello world to file1.txt

Notice that the commit message remained the same because of the --no-edit flag, but the commit ID changed (d0051d1 became c250ab6)! Anytime you amend a commit (or revert and re-commit), Git will make a new unique ID for that commit.

2.2.14. Summary¶

You now know how to version control your files in Git! This consists of:

staging files with

git addcommitting snapshots of your repository with

git commitreverting to old snapshots with

git resetfinding old snapshot IDs with

git log

With these basics, you can start keeping track of versions of your code or files locally over time. So far we’ve learned to use Git on our local computer. In the next lesson, we will learn how to back up our repository.